Capture or Escape of a Photon at a Black Hole: as a trajectory r(t) and as a path r(φ)

By Alexander Gofen (2025)

|

Abstract

We study the Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) representing the static path r(φ) and the trajectory r(t) of light approaching a (non-spinning) black hole in a lab frame of the Schwarzschild model. In the vicinity of a black hole, a light ray dramatically bends. Expressing the path of light via ODEs near a black hole is possible due to the Schwarzschild solution of the Einstein equations of the General Theory of Relativity. We explore those ODEs and graph their solutions using the Taylor Center ODE solver. Some remarkable features of those ODEs present a particular interest for teaching and a challenge for numeric integration. |

The motion as a trajectory r(t)

The motion as a path r(φ)

Comparison: the Newtonian vs. relativistic motion of a particle

Preface

Since the beginning of science and mathematics, the light rays were viewed as the best physical realization of the mathematical abstraction of a straight line. Though a light beam can reflect in a mirror, or bend at the boundary of two mediums, in the vacuum, the light remained the ultimate standard of the very idea of straightness.

However, in 1916 Albert Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity. One of its consequences was that masses bend the curvature of the space, and the light bends too in the proximity of (big) masses. While sounding so bizarre in that time, the new theory predicted a small, but measurable effect of light bending near the Sun.

To measure this effect, astronomers needed a full solar eclipse. Such an eclipse happened in 1919, and the measurement of shifts of stars near Sun disk did demonstrate a small shift merely about one angular second predicted by the theory!

Since then, the light bending has been observed many times while watching remote galaxes, and it was called gravitational lensing. Still, this effect measures only in parts of angular seconds.

In contrast, here we consider effects of light bending in a close proximity to black holes where light ray of a photon can make U-turn or even wind around the black hole before escaping it, or getting caught. It seems fascinating to study such paths of light even if we will never be able to observe them directly.

Here we are to present two models of a photon motion approaching a non-spinning black hole based on the Schwarzschild solution of the Einstein equations of the General Theory of Relativity. Unlike the original equations of Einstein, the Schwarzschild model relies on Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs) available for both static and kinematic models of a photon motion. In the static model the photon motion is given only geometrically as a path r(φ) in polar coordinates, while in the kinematic model it's a trajectory r(t), where time t corresponds to an infinitely remote inertial frame (the lab).

The ODEs of both models are instructive in themselves for the following reasons.

· Their right-hand sides contain square roots whose both branches are required for representing some of the solutions. However

· It's possible to get rid of the square roots transforming the ODEs into the regular (holomorphic) second order ODEs.

· Numerical integration of the ODEs presents a challenge with the critical value of b = bcrit near the circular orbit even despite the 63-bit mantissa because of catastrophic subtractive errors.

· Both ODEs have a remarkable separatrix a circular solution, separating other families of the solutions.

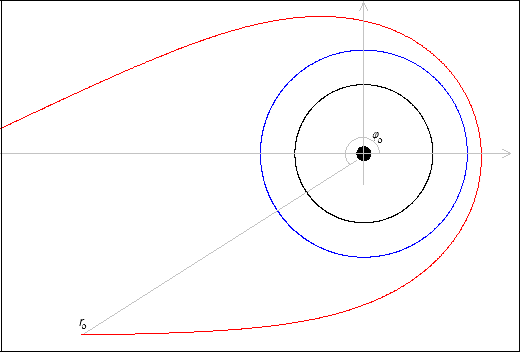

Our setting is this:

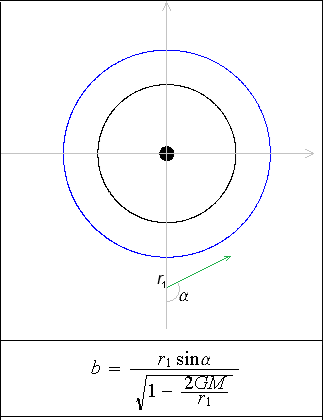

The origin of the polar coordinates is in the center of the black hole. The black circumference is the horizon whose radius is 2GM, while the blue circumference is the so-called circular orbit whose radius is 3GM (here G is the gravitational constant, and M the mass of the black hole).

|

In this study we discern the local path r(φ) of a photon as a geometric curve vs. a trajectory r(t) of the photon as it is theoretically perceived in the time t of a remote inertial frame. It appears that a shape of the trajectory r(t) coincides with the path r(φ), as we will prove later. |

Both models of photon motion for r(t) and that for r(φ) use a special impact parameter b = L/E, where L is angular momentum, and E the energy of a photon at the infinity. It is proved in the theory that value b is conserved along entire trajectory. However, formula (1) in Fig. 2 defines b and makes sense only for points outside of the horizon.

|

|

(1)

|

Fig. 2

For convenience, here we chose the point (r1, 3π/2), where r1 and α are arbitrary, r1 > 2GM, however, formula (1) defines the parameter b for any point (r, φ) where r > 2GM . The values α = 0 or α = π mean that the photon moves exactly along the line connecting it with the center so that b = 0.

|

The fact that the value of b is conserved along the path once it has been chosen means that the angle of direction α is actually a function α(r) implicitly defined by formula (1) outside of the horizon where r > 2GM. Inside the horizon, the value b needed for the ODEs below, must be computed by its definition b = L/E. |

The parameter b corresponds to the tangential component of the direction of motion of a photon given by the angle α. When α = π/2, b expresses purely tangential motion for any point (r, φ). The direction of the radial motion (inbound or outbound) is defined by the proper choice of sign of the square roots in the formula (2) for r(t), or (5) for u(φ) = 1/r(φ) below.

The meaning of b is the same in both models. In particular, we distinguish the critical value bcrit = 3GM√3 delivered by formula (1) for r1 = 3GM and α = π/2 at points (3GM, φ) for any φ on the circular orbit. The solution corresponding to this point is the circular orbit. With b = bcrit, the circular orbit separates the inbound and outbound orbits corresponding to various initial values r and α, as we will see further. With b ≠ bcrit, orbits cross the circular orbit.

We distinguish three special areas (Fig. 2):

· Area A outside of the circular orbit;

· Area B between the circular orbit and the horizon;

· Area C inside the horizon.

Properties of the solutions depend on the areas A, B, C, as we will show later.

Wishing to utilize the real-time graphing of the Taylor Center, we are particularly interested to begin with visualizing the ODEs (2) modelling the time dilation of the trajectories r(t) when approaching the horizon.

|

In order to run all the graphs here as simulations, you have to download and install the application TCenter for Windows, and download and unzip the script files of all the simulations. In simulation of the trajectories r(t), the bullet standing for the photon, moves with the velocity proportional to the velocity of the photon (as perceived in an inertial lab). However, in simulations of r(φ), a velocity of the bullet has no physical meaning. |

The simulations for the section below are in the subdirectory \r(t).

The ODE for u(φ) is simpler and more elegant. We will explore it afterwards.

The motion as a trajectory r(t)

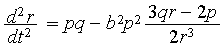

The original ODEs of a photon trajectory r(t) are

|

|

(2) |

Remark 1: The " ± " ODEs for r(t). The ODE (2) for r contains the square root in the right-hand side with double signs representing the two branches of the complex square root. Despite that, the solution r(t) is a single holomorphic solution of these ODEs.

|

How do we know that r(t) is a single holomorphic solution of these singular ODEs? Because r(t) is also a solution of holomorphic ODEs (3), just as u(φ) is a solution of holomorphic ODE (6) so that both r(t) and u(φ) are holomorphic even at the point where the square roots turn zero. |

The two branches in the right-hand side represent the decreasing and increasing segments of the same solution r(t). Moving outbound in area B, r(t) increases satisfying ODE (2) with "+"sign until possibly reaching the maximum, after which r(t) decreases satisfying ODE (2) with ""sign. Moving inbound in area A, r(t) decreases satisfying ODE (2) with ""sign, until possibly reaching the minimum, after which r(t) increases satisfying ODE (2) with "+"sign.

Remark 2: "Removable singularity" of the ODE. ODE (2) has a branching singularity when the under-the-root expression becomes zero and this may happen. However, as we will demonstrate later, the ODEs for r(t) or r(φ) belong to those remarkable ODEs, which, despite being singular, have regular solutions. An example of such an ODE is x'(t) = nx/t which is singular at t = 0. However, for natural n, it has a holomorphic solution x = tn. Besides, there exists also a regular ODE x' = ntn 1 having the same solution. We will see, that for the holomorphic solutions r(t) of (2) and u(φ) of (5), regular ODEs without a square root also exist.

Remark 3: Specialty of this regularity. We know, that some functions expressed as a superposition of two functions, are holomorphic despite that one of the two is singular. For example, f (z) = cos(√z) is holomorphic at z = 0 despite that √z is singular at zero. Here the external holomorphic function cosine "kills" the singularity of the internal one. In the holomorphic functions r(t) or r(φ), derivatives r'(t) and r'(φ) (or u'(φ)) are holomorphic too. We will see, that both radii may have extremal points in areas A and B so that r'(t) = 0 or u'(φ) = 0 both expressed as square roots in formula (2) r'(t) = √g(r) and (4) u'(φ) = √f(φ). In them, the under-the-root functions g(r) and f(φ) are holomorphic. However, despite that the square root is singular at zero, these superpositions are holomorphic. I.e. now it is the internal holomorphic function that somehow kills the singularity of the external one. What kills the singularity in this case? The special properties of the under-the-root functions g(r) and f(φ). Not only don't they ever get negative under the root, but even when they do reach zero at extremal points, the analytic continuation of r'(t) and u'(φ) smoothly transitions from one branch of the square root to the other.

Remark 4: When to switch the sign. The solution r(t) may have an extremal point where r'(t) = 0 because the under-the-root expression turns into zero. If this is the case, r'(t) in (2) must change the sign going over this point. This translates into the necessity to switch the sign at the square root, both branches of which represent the same holomorphic solution r(t). An attempt to integrate ODE (2) with the Taylo method over this extremal point would fail, but we will integrate a regular ODE (3) instead.

Remark 5: A quadrature. Here the ODE (2) in r is uncoupled, and the variables t and φ are absent in the right-hand side of it. As such, it has a quadrature the integral expressing t(r).

Theorem 1: The ODE (2) (or ODE (3)) has two families of special solutions:

a) For any point (r = 2GM, φ) on the horizon, φ and b being arbitrary, the exceptional stationary solution r = const = 2GM, φ = const, r', φ' = 0 satisfies ODE (2). The horizon is a locus of such stationary solution-points.

b) For any point (r = 3GM, φ) with b = bcrit and φ arbitrary, the exceptional solution r = const = 3GM, r' = 0, satisfies ODE (2) representing the circular solution coinciding with the circular orbit.

Proof: (a) It's easy to see that this system has a stationary motionless solution r ≡ 2GM and φ ≡ const, representing any point on the horizon. At any such point, for an observer in a remote inertial lab, the photon will be perceived as motionless, and the time stopped. Any solution approaching the horizon would asymptotically approach such a point. If the numeric integration were infinitely accurate, we would see just that r(t) → 2GM and (1 2GM/r) → 0 while always remaining positive. However, due to inevitable rounding errors and finite number of digits, at certain step the parenthesis gets negative so that the further integration evolves into a numerical artefact with radius r increasing (making no physical sense). This is the first family of special solutions.

(b) Now consider the under-the-root expression in ODE (2). For b = bcrit = 3GM√3 and r ≡ 3GM, the under-the-root expression turns into identical zero, proving the case (2). ■

Corollary 1: In case (a), no other solution in areas B or C can reach any point on the horizon, because any point on the horizon is a (stationary) solution in itself of the holomorphic ODE (3), which surely meets the conditions of existence and uniqueness of solutions. If another solution r(t) reached a point t0 of the horizon having r'(t0) = 0 because of the parenthesis in (2), it would be violation of the uniqueness. Therefore, the points of the horizon form a locus of points unreachable and impenetrable from the areas B and C. This locus (the points of the horizon) obviously separates all solutions in B from the solution in C. Yet the horizon is not a separatrix because the horizon (as a circumference) is not a solution: each of its point is.

Corollary 2: In case (b), if we consider a family of solutions in both areas A and B all having b = bcrit, neither of those solutions can reach the circular orbit for the same reason of the existence and uniqueness of the solutions of ODE (3). In this case, the circular orbit is a solution, therefore it plays a role of an unreachable and impenetrable separatrix between the solutions in area A and those in area B. However, if b ≠ bcrit, the trajectories can cross the circular orbit penetrating from area A to B and vice versa unlike the horizon, which is impenetrable for any values of b.

See here for more theorems concerning these ODEs and their solutions.

In order to rid of the square root, let's transform the ODE (2) into a second order ODE by differentiating both sides of (2). Such a differentiation is particularly simple when applied to an ODE of the format r' = √f(r). Then

|

r" = |

f'(r)r' |

= |

f'(r)√f(r) |

= |

f'(r) |

|

|

2√f(r) |

2√f(r) |

2 |

|

In our case, f(r) is the result of placing the external parenthesis of formula (2) under the square root. With that in mind, we will get a second order ODE

|

|

(3) |

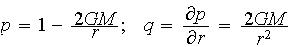

where

The required initial value for dr/dt is obtainable from the respective ODE (2) at any regular initial point with the appropriate choice of the sign to specify the inbound or outbound direction. This is the only usage of ODE (2).

In terms of r, φ, the speed c of photon in a remote inertial frame is

![]()

containing time derivatives of r and φ so that the speed of a photon (in the lab frame) varies in the vicinity of the black hole (rather than being the known constant c of the speed of light in the vacuum afar from any masses).

Below are results of integration of these ODEs for several special settings.

Inbound motion from Area A toward a black hole.

Preliminary notes: distinction of trajectory vs. path.

1. The trajectory r(t) and the path of a photon r(φ) geometrically coincide everywhere when they both exist, however they do not always both exist: r(φ) is "omnipresent", r(t) is not.

2. The path r(φ) of a photon moving from infinity inbound, may penetrate both into areas B and C nearly approaching the origin. From there, this curve may be integrated in φ also backward, however the photon in area C can never move away from the center.

3. The trajectory r(t) can never reach the horizon and penetrate into area C. If a problem for r(t) is set inside area C, the photon can move only toward the center no matter the value of b.

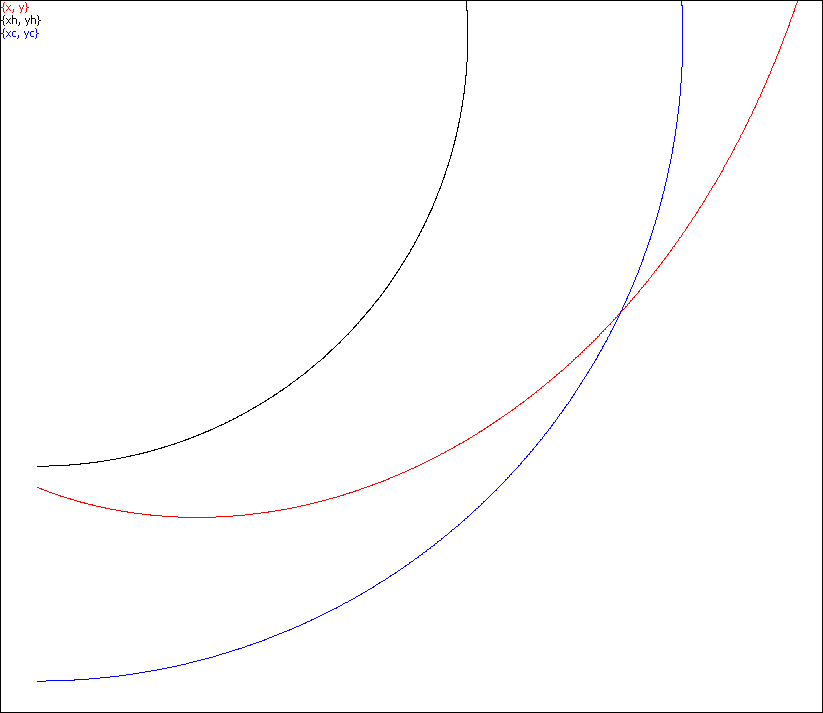

Here we consider a trajectory r(t) of a photon moving from infinity in area A towards a black

As the function r(t) in this scenario initially must decrease, we must choose the sign "" in ODE (2) (whne setting the initial velocity).

Then, a photon moves either along a spiral so that it is caught, or along a curve similar to a hyperbola when it escapes.

If the photon moves along a spiral to be caught, r(t) has no minimum, r'(t) < 0 so that the under-the-root function g(r) > 0. At that, it moves along an infinite spiral approaching and winding around and approaching the circular orbit asymptotically, i.e. being caught by the circular orbit; or it moves along a finite spiral being caught by the horizon of the black hole (even though r(t) only asymptotically approaches the horizon never crossing it as perceived in a remote lab). This scenario takes place when b ≤ bcrit.

If, however, the photon escapes, it remains in area A, means that r(t) reaches its minimum at a certain point outside the circular orbit where r'(t) = 0 so that the under-the-root function g(r) = 0 (remaining non-negative), after what the root must change the sign to "+" so that r'(t) > 0 after that.

Examples

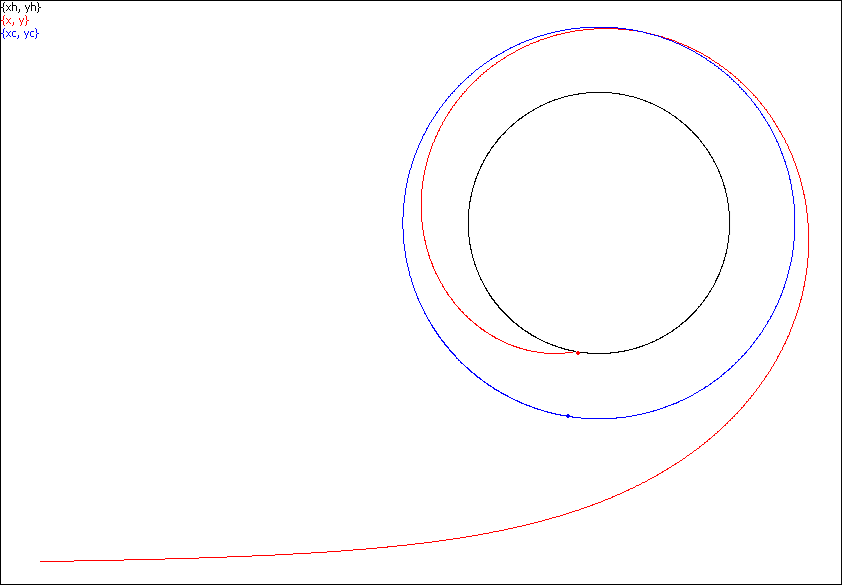

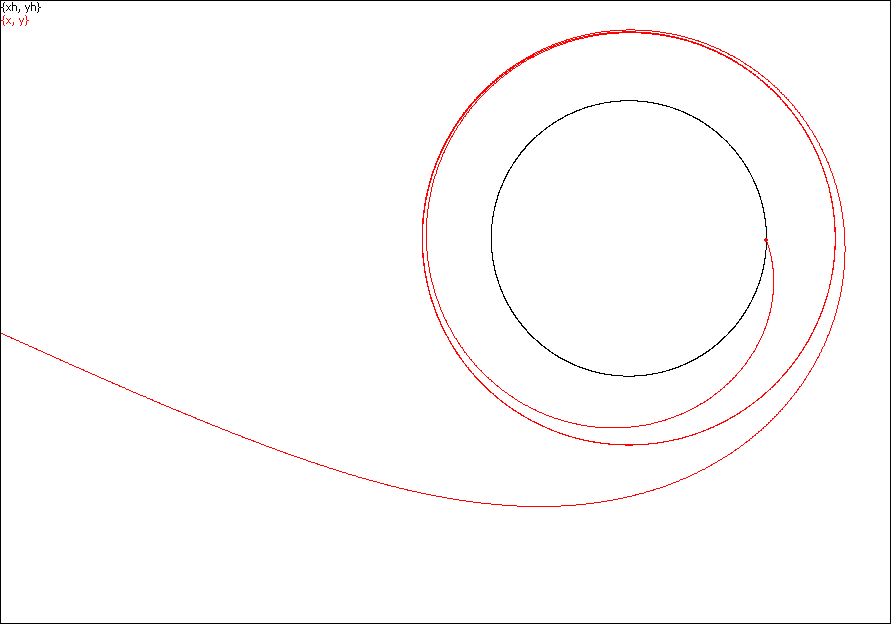

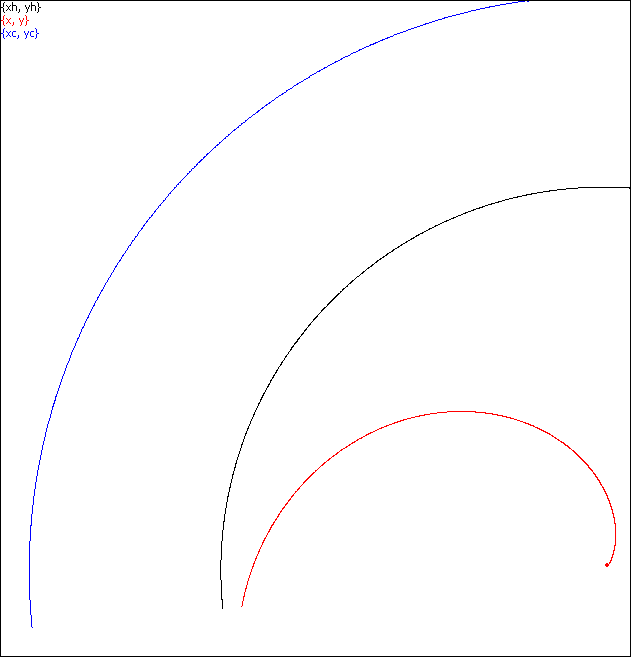

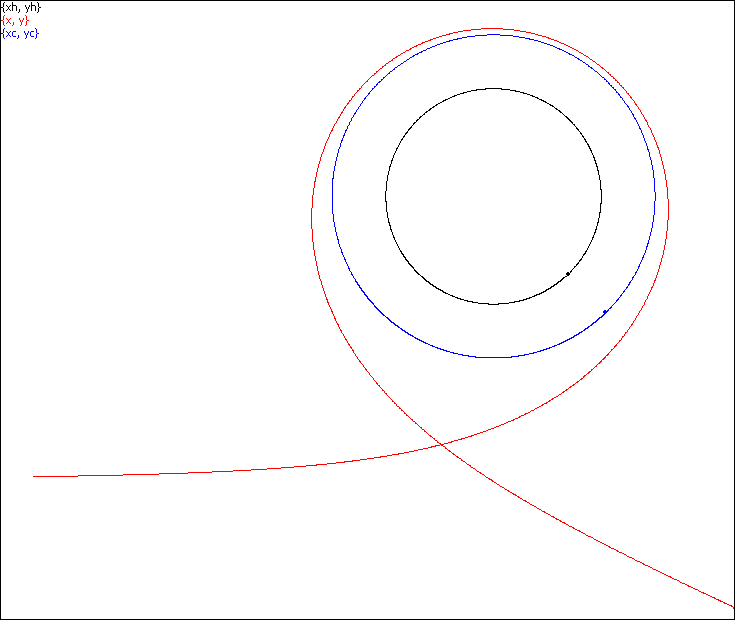

Fig. 3. A typical trajectory of a capture, file tSpiralFall.scr.

The parameter b < bcrit causes a photon (in red) to cross the circular orbit (in blue)

approaching the horizon (in black) in a finite spiral fall.

In this problem, the integration process achieves the highest possible accuracy of all 63 binary digits of mantissa at every step. If you run the script, you will see how the photon slows down and stops approaching the horizon as perceived at a remote inertial lab. In the local frame of the black hole, its motion continues, and its path r(φ) is not interrupted, as we will see in the next section.

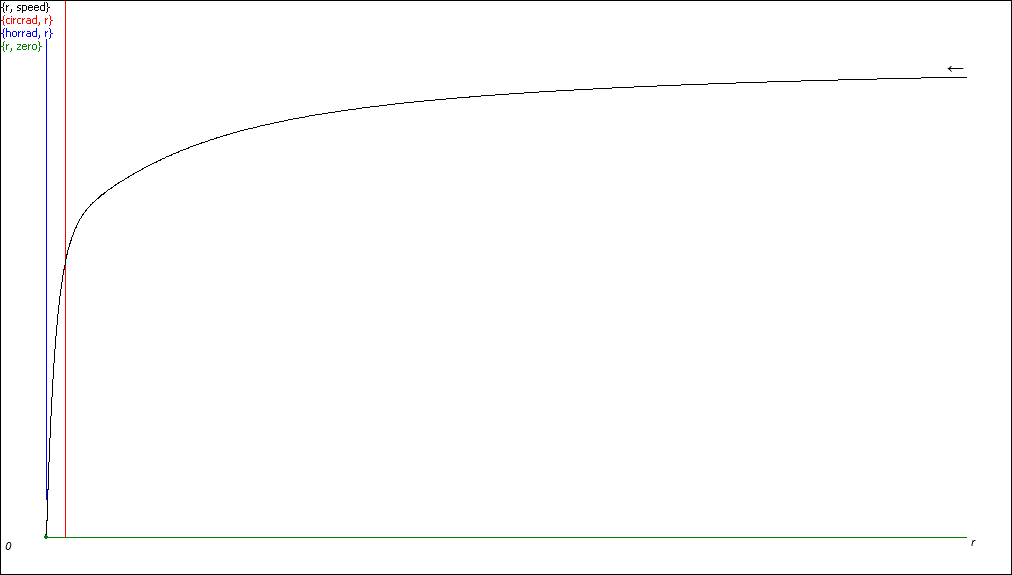

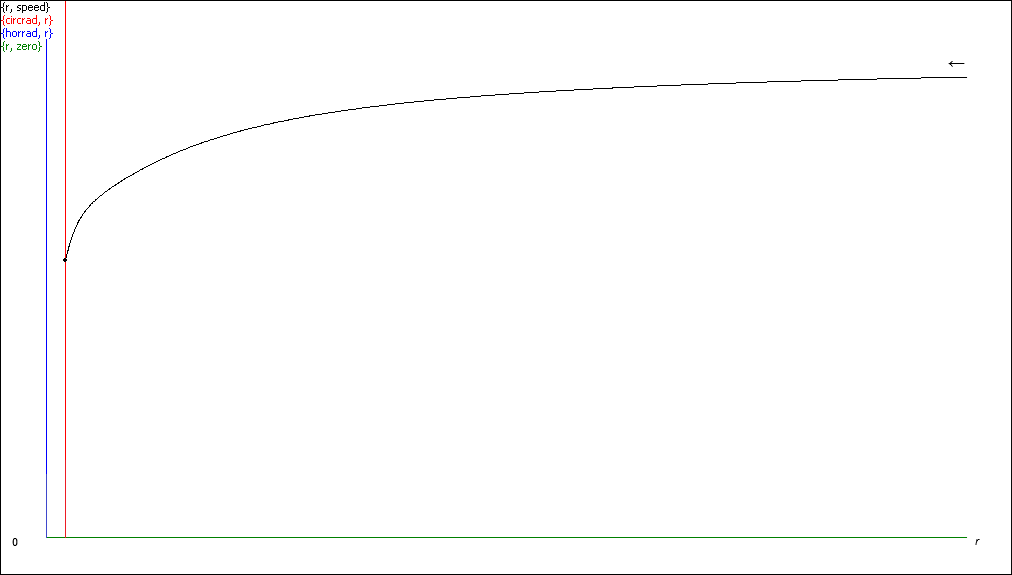

Fig. 4. The graph of the speed of a photon from Fig. 3 as perceived at a remote inertial lab

as a function c(r) of the radius, file rSpeedForSpiralFall.scr.

The photon moves towards the horizon along a finite spiral.

The vertical red line denotes the radius of the circular orbit. The blue line denotes the horizon.

Fig. 5. A typical trajectory of an escape caused by the parameter b > bcrit, file tEsc.scr.

The case when b = bcrit is of a particular interest because then a photon can neither cross the circular orbit, nor bypass it and escape. Instead, when approaching the circular orbit, it winds around it in an infinite tight spiral whose laps asymptotically approach the circumference of the radius 3GM of the circular orbit. Table 1 shows how fast the laps of the spiral approach to the radius 3GM = 3 in a simulation tCircularEsc.scr with b = bcrit.

|

Radii of lapses |

Comments |

|

3.00574180405412858 3.00000909007521786 3.00000001924833304 3.00000000985476543 3.00000511111359953 3.00266147068167067 |

First lap Second lap getting much closer to 3 Third lap gets even closer Fourth lap still closer, however Because of rounding errors, now the radii of laps began to grow |

Table 1. Numerical behavior of radii of laps for b = bcrit

This integration was performed with a relative error tolerance for r and φ as small as 10-20, meaning that all 63 digits of the mantissa were correct at all steps. However, the same requirement for r' could not be achieved because r' → 0 so that a relative error requirement cannot be fulfilled.

As the Table shows, there were only 5 laps instead of infinitely many. In the graph below, the lapses are so tight that they are undiscernible.

A tightness of these laps and its nature are explained here. When r gets closer to the radius 3GM, a ratio between radii of the next and current laps approaches the value e-2π ≈ 0.0018, adding about 3 more zeros after the decimal point (if the integration were ultimately exact).

|

In order that a photon move exactly along the circumference, it must be fired from a point on the circumference r = 3GM tangentially with α = π/2 see the file tCircularExact.scr. |

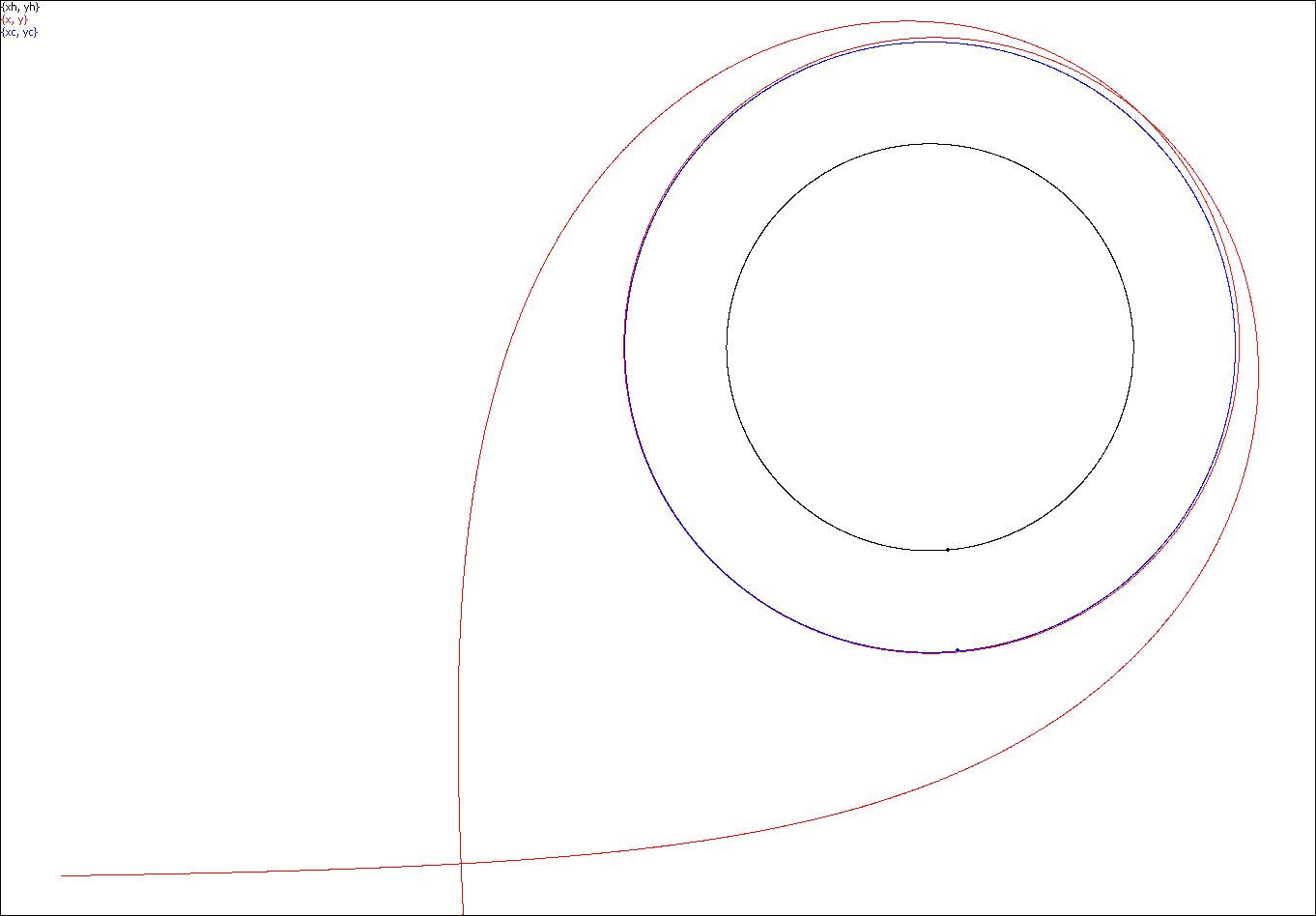

Fig. 5. An escape which should not happen with b = bcrit, file tCircularEsc.scr.

Theoretically, this photon must be caught into a tight infinite spiral winding around the circumference.

Numerically, however, b ≈ bcrit (though 63 binary digits accurate). Therefore,

a rounding error of integration (despite being 63 digits accurate) leads to an escape as if it were b > bcrit.

The photon (in red) makes here 5 laps around the circular orbit, though they are invisible on the graph

because of their tightness. They are observable as a bullet move in the real-time simulation tCircularEsc.scr.

Fig. 6. A capture by the horizon which should not happen with b = bcrit, file tCircularIn.scr.

With b = bcrit, the horizon ought not to be even reached.

Theoretically, this photon must be caught into a tight infinite spiral winding around the circumference.

Unlike on Fig.5, here we intentionally made b = bcrit 0.0000000001

(to evade the escape caused by numeric artefacts with b = bcrit in Fig 5).

The photon (in red) makes here several laps around the circular orbit,

though invisible on the graph because of their tightness, until it falls into the horizon.

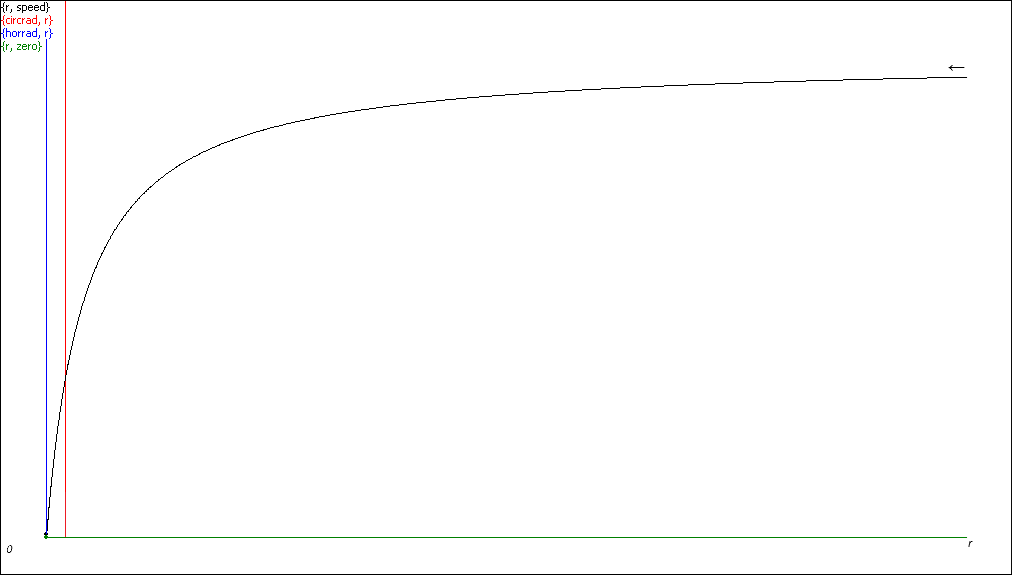

Fig. 7. The graph of the speed of a photon from Fig. 5 before it escapes,

as perceived at a remote inertial lab as a function c(r) of the radius.

The photon approaches the circular orbit in infinite spiral.

The vertical red line denotes the radius of the circular orbit. The blue line denotes the horizon.

Fig. 8. The graph of the speed of a photon which moves towards the center along a straight line (b = 0)

as perceived at a remote inertial lab as a function c(r) of the radius.

The blue line denotes the horizon. The vertical red line denotes the radius of the circular orbit.

Here the c(r) decreases to zero steeper than in other cases above.

A puzzle of the c(t)

Unlike in the previous subsection, here we consider a dependency of the speed of a photon as a function c(t) of time in the remote lab, rather than a function of the distance r to the center.

All three graphs above of the varying speed c(r) of photon are displayed as functions of radius-vector r (i.e. the distance from the center of the black hole). In all those cases we saw that the speed of the photon (viewed in a remote inertial lab) monotonously decreases as the r decreases getting closer to the horizon. At that, all the curves c(r) remain clearly convex.

It's not so for graphs c(t) having inflection points: at least one.

ForCircular.png)

Fig. 9. The graph of the speed c(t) of a photon for the circular approach Fig. 5 (before escape), file c(t)ForCircular.scr

ForStraightLine.png)

Fig. 10. The graph of the speed c(t) of a photon for the strait line approach to compare with Fig. 8, file c(t)ForStraightLine.scr

These two graphs above have one inflection point.

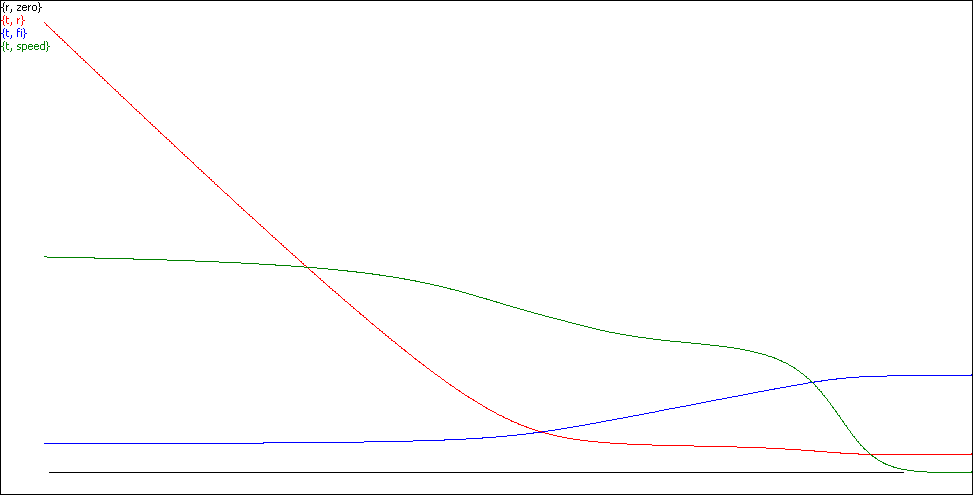

Now take a look at this combined graph of photon speed c(t) (green) to compare with Fig. 4, corresponding to the case Fig. 3 when a photon moves along a finite spiral towards the horizon.

Fig. 11. Here φ(t) is blue, r(t) is red, and photon speed c(t) (displayed magnified 25 times) is green, file c(t)SpiralFall.scr.

All three graphs are still monotonous, however, unlike before,

now c(t) switch convexity/concavity in the process twice.

Why is the case of finite spiraling different?

The expression for the speed of photon is

The points of inflection of the function c(r) are zeros of ∂2c/ ∂r2 a rational function whose numerator is a polynomial with a degree > 4.

The points of inflection of the function c(t) are zeros of d2c/ dt2 a rational function whose numerator is a polynomial with a degree higher than that of ∂2c/ ∂r2. Meanwhile, we do not explore this problem further.

Outbound and inbound motion from area B: capture or escape.

Subfolder: \AreaB

Here we will take a look at a few examples how photon can escape away from a very close vicinity of a black hole slightly outside the horizon while inside the circular orbit (area B).

If a photon was fired away slightly outside of the horizon, its chances to escape depend on the direction of firing controlled by the parameter b. It surely escapes if fired away exactly along the radius so that b = 0. Otherwise, the outcome depends on b (or the angle α in b).

Escape from a point in area B near the horizon: b < bcrit, files tEsc0.scr, tEsc1.scr.

Capture from a point in area B near the horizon: b > bcrit , file tNearEsc.scr

Capture of a photon fired from a point in area B near the horizon with b = bcrit. File tNoEscCritical.scr.

The trajectory is an infinite tight spiral approaching the circular orbit infinitely close from inside.

Capture of two photons: one (in blue) fired outbound from a point near the horizon,

the other (red) fired from outside inbound: both with b = bcrit. File tCriticalFromBothSides.scr.

The two trajectories are infinite tight spirals approaching the circular orbit infinitely close from inside and outside.

In area C.

Subfolder \AreaC

If a photon moving from area A was not captured into the circular orbit, physically, it would bypass area B and move on into area C to the center along a path defined by a solution r(φ). However, from the point of view in a remote lab according to the solution r(t), the photon would stick in the horizon forever. In a remote lab it's physically impossible to know what happens with this photon in reality when it is inside area C. The simulations InsideAreaC.scr and InsideAreaCStraight.scr help to visualize this.

In area C formula (1) for b does not apply so that b must be set from physical considerations. Whichever the value of b, inside the horizon the photon can move only in such a manner that the radius decreases, so that the initial value for r' must be set negative with the sign "" at the square root.

In both simulations, the photon is fired from the point inside area C near the horizon: r = 1.9 < 2. The concept of direction here is inapplicable, however, the value of b may vary from 0 to infinity.

At that, the value b = 0 sets the strictly radial motion of a photon toward the center with noticeable "acceleration" at the center (in the simulation). The word "acceleration" here is in quotes because physically the photon always moves with the speed of light c. It's merely the property of the Schwarzschild coordinates in which r(t) demonstrates variation of speed perceived in those coordinates.

A value b = 10 (or whichever big number) adds a tangential component to the motion, but still in such a way that a photon moves toward the center along a finite spiral as in the figure below, with noticeable "acceleration".

In this picture a photon was fired from the point inside area C near the horizon: r = 1.9 < 2.

The simulation InsideAreaC.scr demonstrates that at the beginning the photon nearly "rests" and then steeply "accelerates".

Between areas A and B.

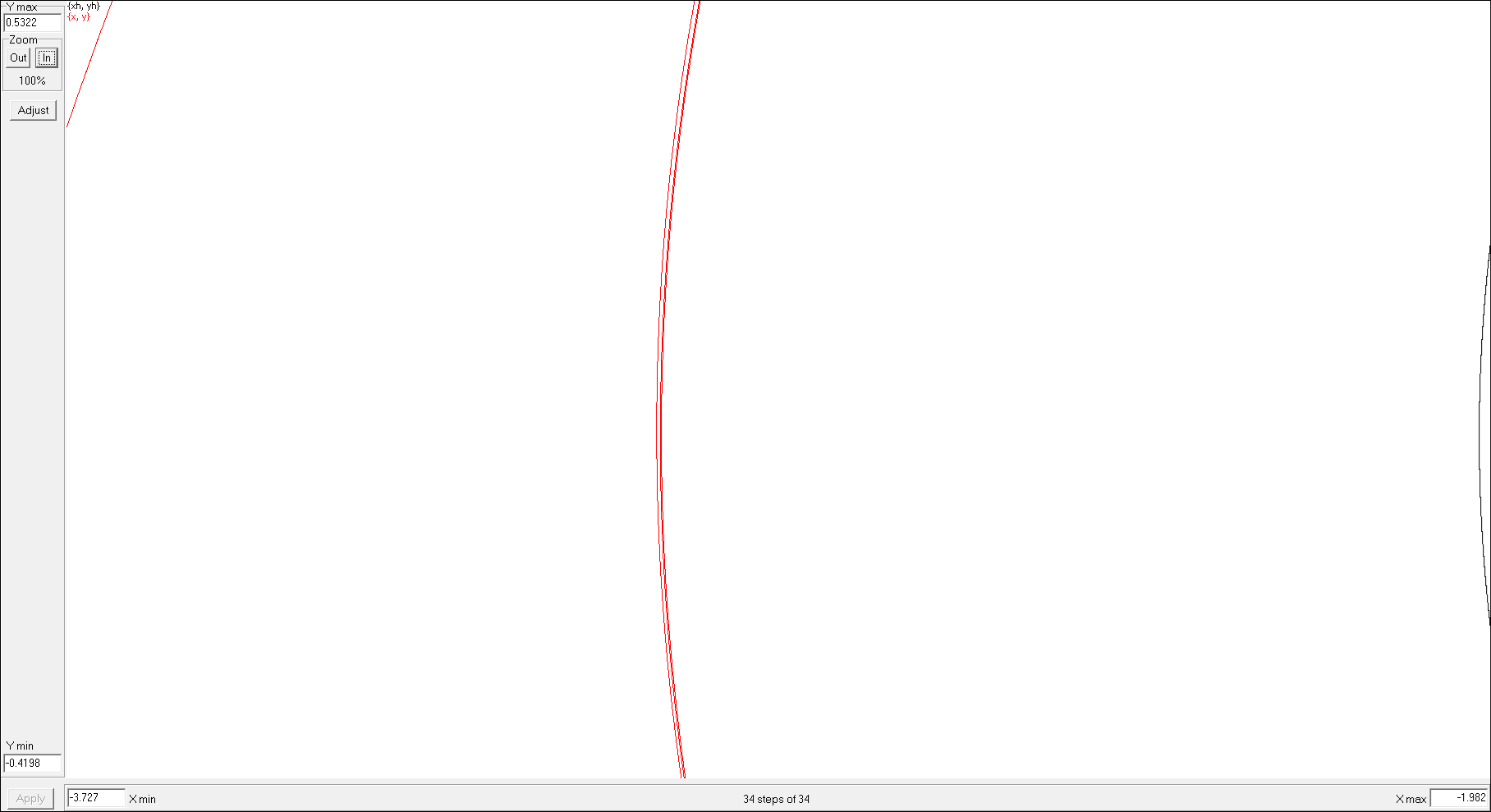

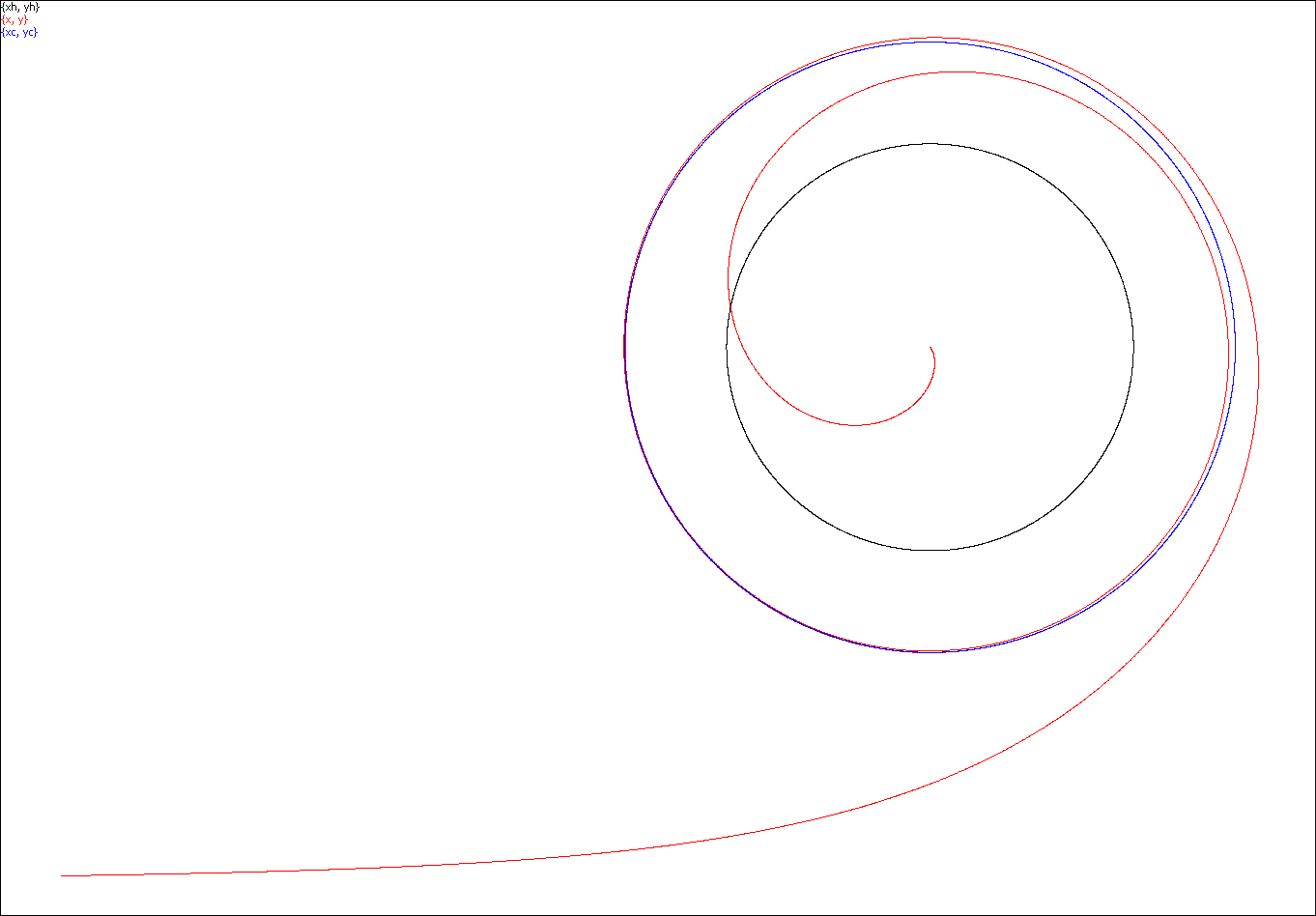

Below there is a zoomed-in picture of a fragment of an infinite spiral of a photon path with b = bcrit being captured by the circular orbit.

This is a zoomed-in image demonstrating tightness of the infinite exponential spiral

winding around the circular orbit. Because the spiral is exponentially tight, only first 3 laps are discernible.

|

In this section the motion is modelled as a path r(φ) so that an independent variable t of time is absent. Therefore, real-time playing via the button Play is senseless and does not display meaningful animation. |

The simulations for this section are in the subdirectory \r(fi).

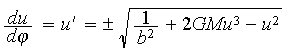

In this model the ODE is simpler. The ODE, as originally written for u(φ) = 1/r(φ), is:

|

|

(5) |

Remark 6: Here the variable φ is absent in the right-hand side so that this ODE has a quadrature as an integral for φ(u).

Remark 7: Also here, at the point when the distance rmin of a photon to the origin gets minimal (and umax= 1/rmin gets maximal), it must be that du/dφ = 0, possible only if the under-the-root expression becomes zero the singularity of the root. An attempt to integrate this ODE until point rmin would inevitably fail. We must try to get rid of the square root also here.

As before, we transform (5) into an ODE of order two eliminating the radical:

|

u" = 3GMu2 u

|

(6) |

Not only is this ODE simpler than those for the temporal model, but it also uncovers a deeper reality: literally.

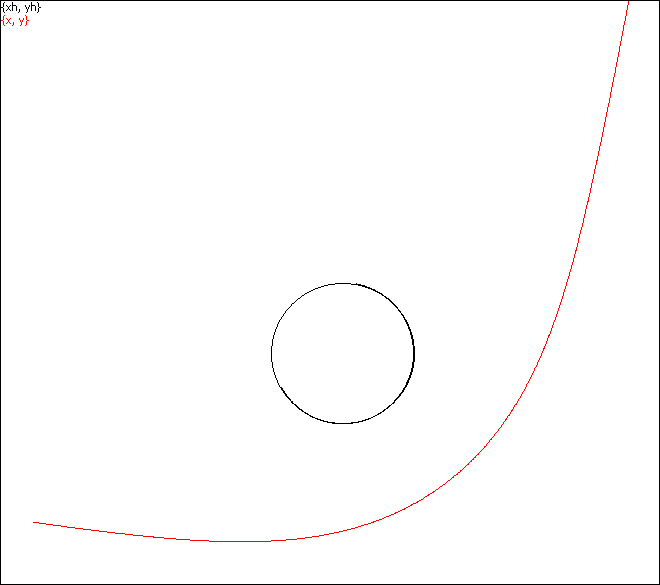

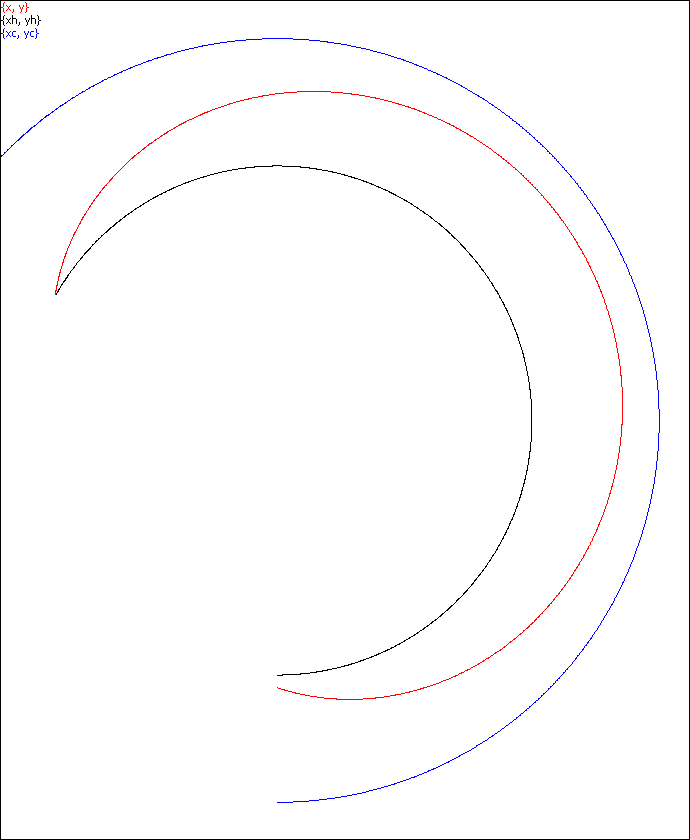

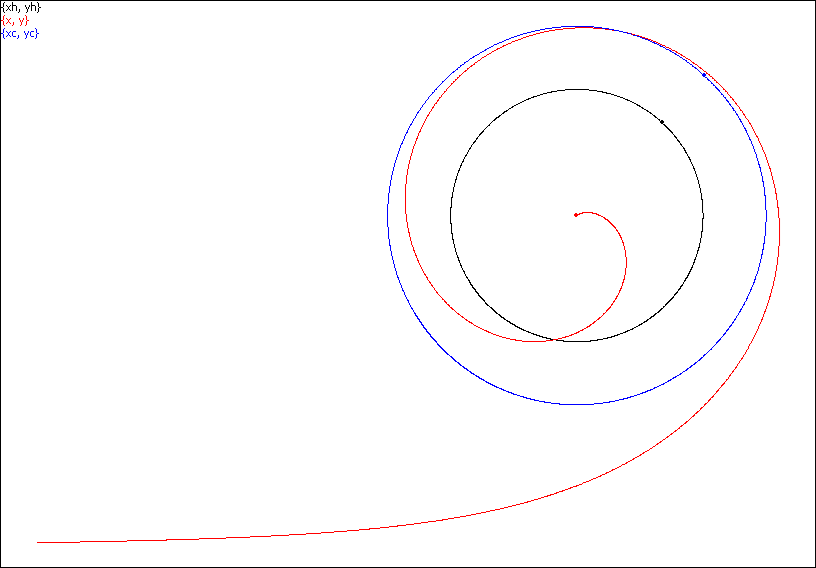

This picture replicates the case of a spiral fall Fig. 3 considered above, file fiSpiralInsideHorizon.scr.

However, unlike there

Now the red path of a photon penetrates inside the horizon approaching the center of the black hole.

This is possible because, unlike the temporal model above, where the lab time stops at the horizon, this ODE describes merely the path of the photon motion which surely moves on also after crossing the horizon.

Here a photon makes a U-turn, file Uturn.scr.

And here the path replicates letter γ upside-down, file Gamma.scr.

The accuracy challenge

When b = bcrit, the right-hand side 3GMu2 u of the ODE (6) approaches zero when u approaches 1/3GM the circular orbit. Both terms in the right-hand side are finite values, but their difference gets closer and closer to zero, leading to the situation of the so-called catastrophic subtraction error in the derivative u" = 3GMu2 u. With every next lap of the spiral, the accuracy of u" drops more and more, until this error causes a numeric deviation from the circular limit, so that both the trajectory r(t) or the path r(φ) goes astray.

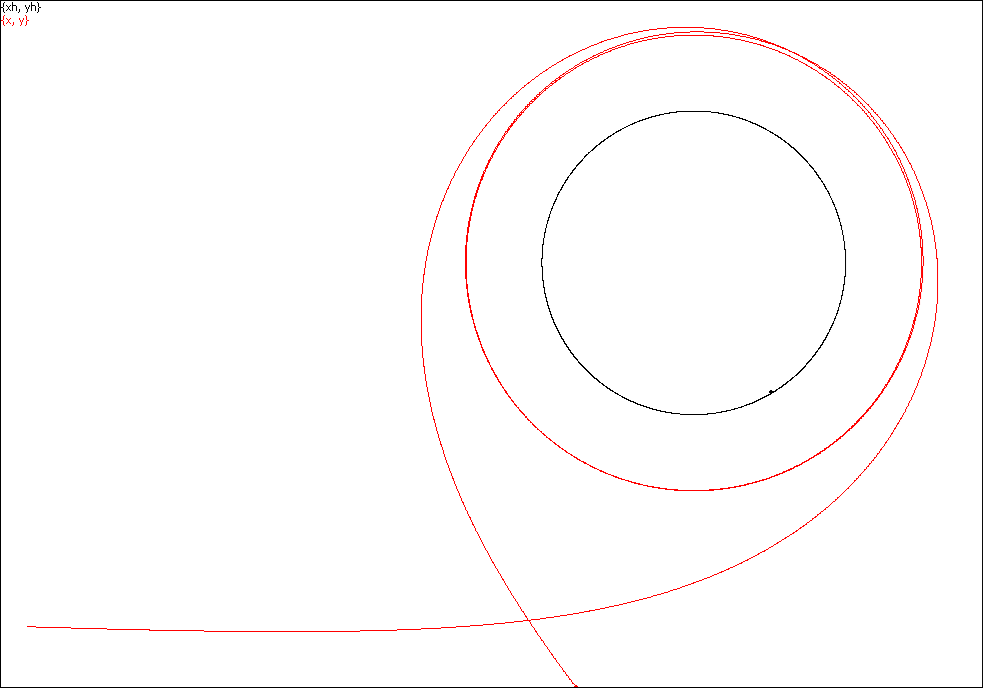

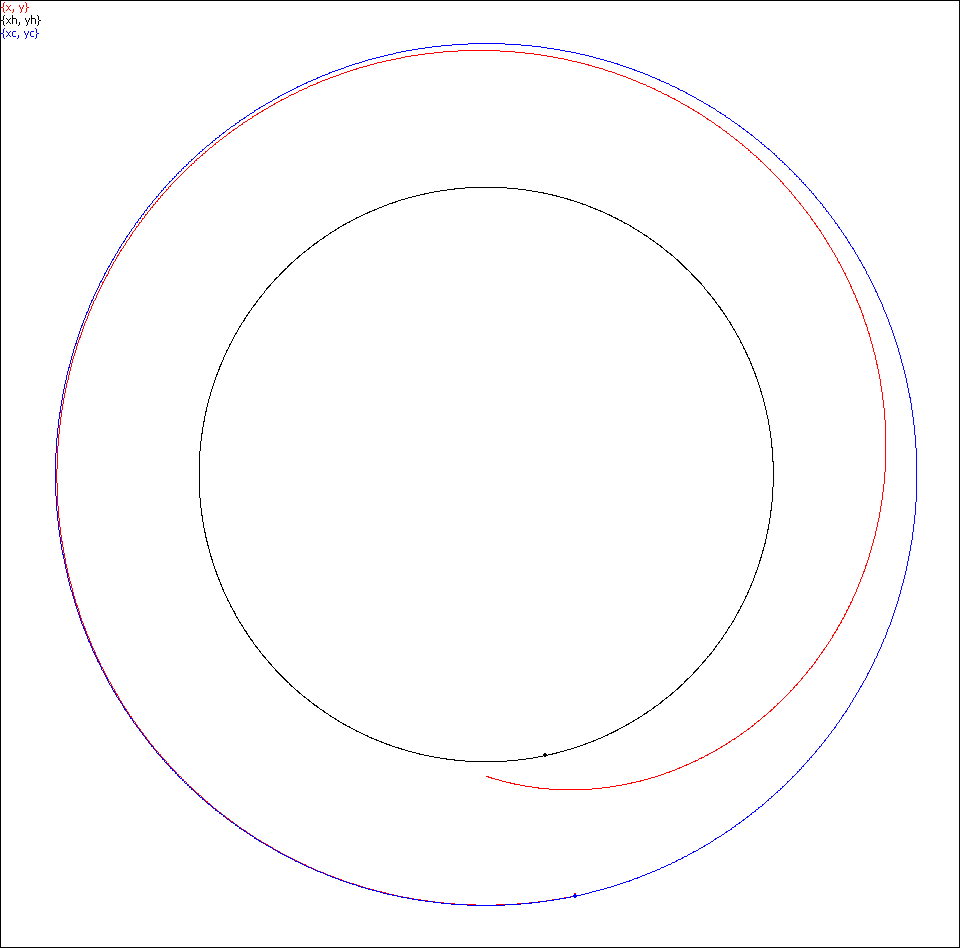

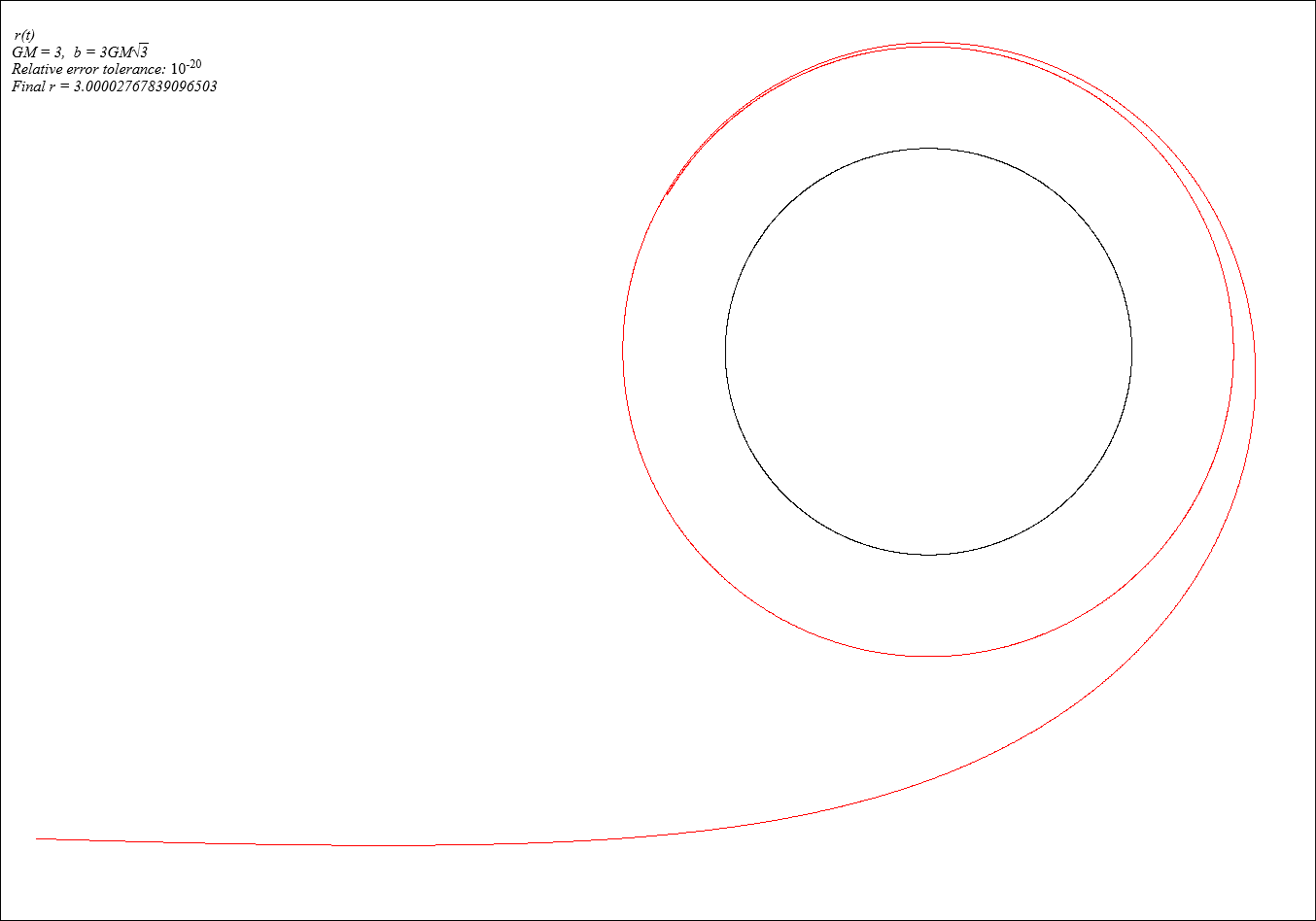

Here is the case with b = bcrit = 3GM√3, and the initial r > 3GM outside the circular orbit.

We know that this solution must wind around the circular orbit closer and closer never escaping.

However, due to integration errors in the mode of default error tolerance,

the path deviates into an erroneous orbit of escape.

This is the same case with b = bcrit = 3GM√3, and the initial r > 3GM outside the circular orbit.

However here it was integrated with the smallest relative error tolerance

meaning that all 63 binary digits in the mantissa are enforced to be correct.

Now this correctly integrated solution very tightly winds around the circular orbit,

closer and closer, never escaping, as it should.

Approach to and capture by the circular orbit

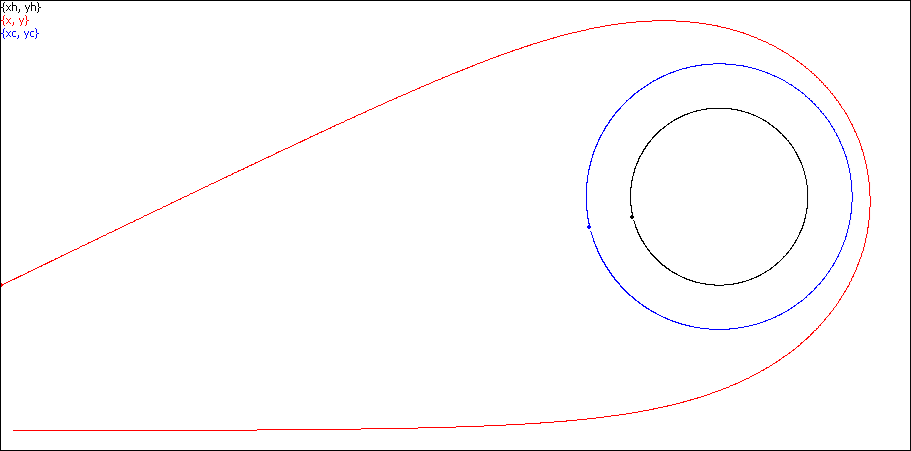

Comparison: the Newtonian vs. relativistic motion of a particle

In the 19th century, before the theory of relativity by Einstein, physicists surmised that the light particle under gravity would move in accordance with the Newtonian laws, like any other particle, with the only particularity that the speed of light particle is enormously high (as it was already known then). With that in mind, the physicists expected that a light ray would slightly bend when closely bypassing Sun. The trajectory of light near Sun, therefore, would be a hyperbola, though bent so little that the instruments of the time would not detect it.

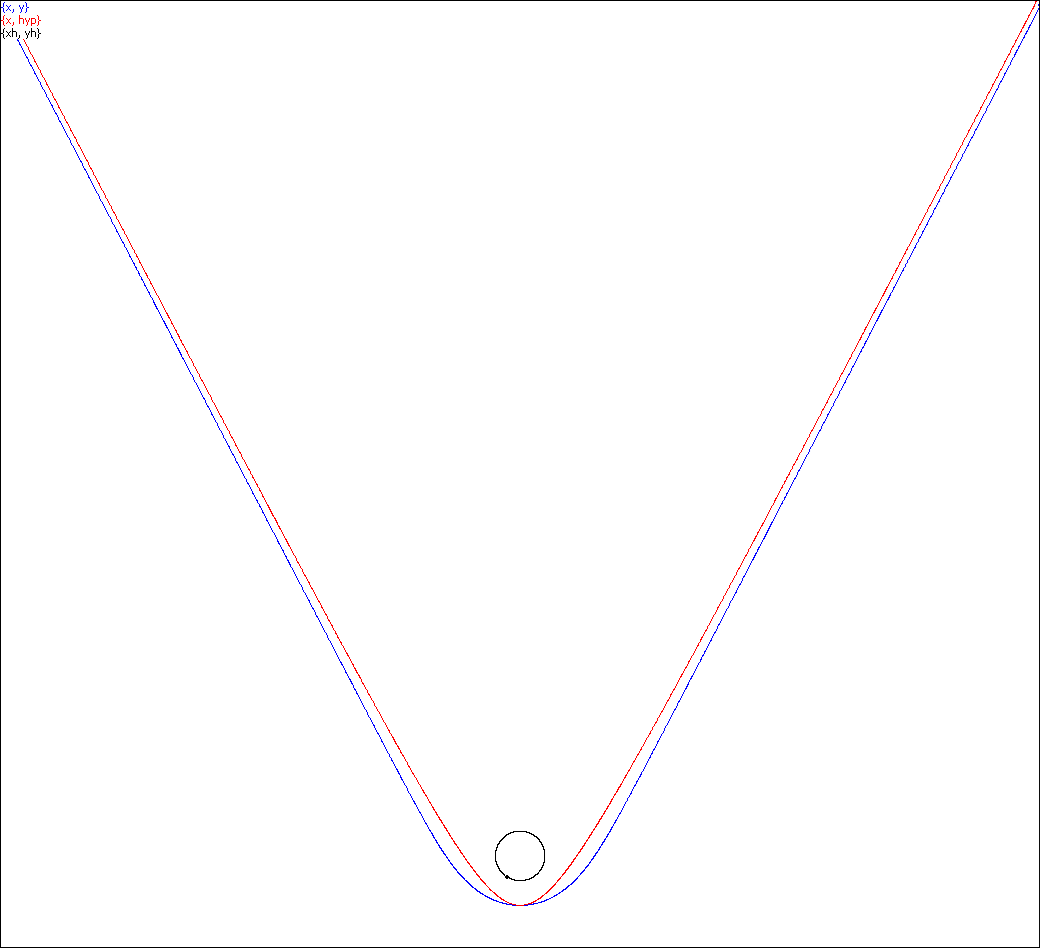

After emergence of the General Relativity and the Schwarzschild solution, it became clear, that the trajectory of light is not a hyperbola, though its shape does resemble a hyperbola (see the figure below).

A path of a photon (in blue) vs. a hyperbola (in red). The horizon is in black.

See the simulation PhPathVsHyperb.scr

|

A particle under the Newtonian gravity |

A photon in the General relativity |

|

The trajectory is determined by the direction and the speed of a particle. |

The trajectory is determined by the direction of the emitter only as the speed of light in vacuum remains constant. |

|

The trajectory is always one of the three conics: ellipse (including a circle), hyperbola or parabola. |

Only a circular orbit having one specific radius is possible, while the other conic orbits are not. |

|

The circular orbit is achievable at any distance from the pointed mass, providing that the initial velocity is tangential and has the proper value. |

The circular orbit is achievable only at the distance 3GM (3/2 of the horizon radius) providing that a photon is emitted tangentially at the circular radius 3GM only. |

|

No orbit is an attractor. |

The circular orbit is an attractor. An orbit of a photon moving from infinity toward a black hole in certain direction, or from inside out, spirals into the circular orbit attracted by it. |

|

A particle escapes depending on its speed and direction if the initial speed exceeds certain value. While escaping, the particle moves along a parabolic or hyperbolic orbit. |

A photon escapes depending only on its direction and the initial position. If it approaches from infinity, a shape of the escape orbit resembles a hyperbola, though it is not a hyperbola. |

|

Otherwise, it moves along an ellipse. |

Otherwise, the photon approaching from infinity is either caught into the attracting circular orbit, or crosses it moving into the inside of the horizon. |

A comparison table.

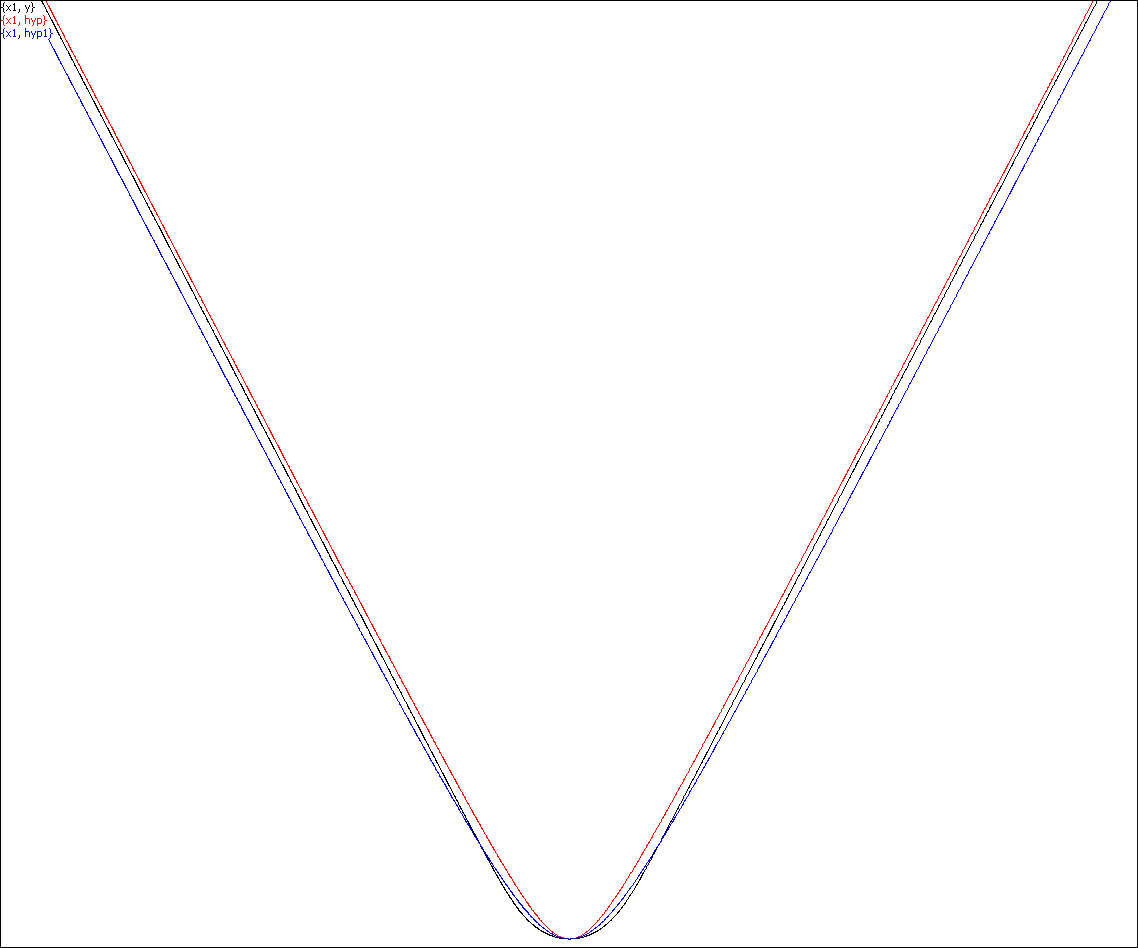

A path of a photon (in black) vs. two hyperbolas (PhPathVs2Hyperb.scr):

in red a more sharp, in blue less sharp, crossing the photon path.

Formula.png)